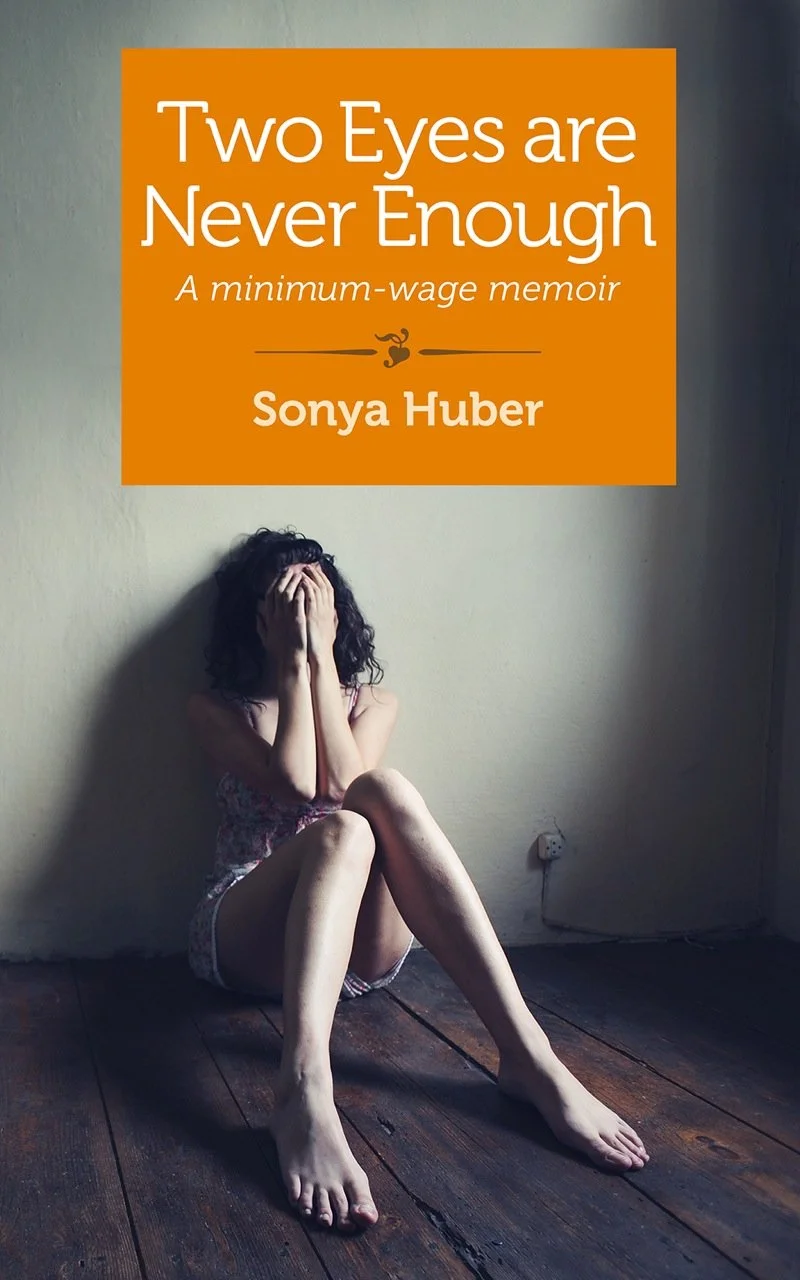

Two Eyes Are Never Enough

My ebook on direct care workers is now available from SheBooks!

My ebook on direct care workers is now available from SheBooks!

Two Eyes are Never Enough: A minimum-wage memoir

This piece is the length of a long magazine article, and it explores the world of direct care workers, those who work in nursing homes, residential care centers, and mental health facilities. They are often immigrants, often women of color, usually working for very low pay. I once did that work, which got me interested in the first place. That's why the piece is called a memoir, though there's a good chunk of reporting in there too.

How to Support Direct Care Workers

Much of this little e-book is about the physical and emotional labor of caring for others, particularly those in crisis. It's hard work, sometimes physically dangerous, yet often very low-paying; in fact, home health care workers--one category of direct care workers--are not even covered by minimum wage legislation, which is outrageous. Yet there are many organizations advocating to change this. One huge victory came about late last year, when legislation was passed to cover these workers, which have been left out of wage protection since 1974. This ruling is scheduled to go into effect on Jan. 1, 2015, but there are twists and turns ahead: it was just reported last Saturday in the New York Times editorial page ("No Reason to Delay Fair Wages," 5/17/14) that a group representing state Medicaid officials is asking for a delay in implementation.

As the editorial states:

"Sixteen states already require that home care workers be covered under state wage and hour laws, so there is a template for how to apply the federal rule. The rule change was researched and analyzed for almost two years before being finalized last September... Any delay would further the exploitation of home care workers--mostly women, minorities and immigrants--who bathe, dress, and feed elderly and disabled clients and assist them with other daily activities. For-profit home care agencies that pay subminimum wages or deny overtime and state Medicaid officers accustomed to balancing their budgets on the backs of underpaid labor will have to get used to paying more."

If you're interested in getting active on these issues and adding your voice, consider supporting one of these organizations:Caring Across Generations: A coalition of nonprofits and unions working for legislation and public attention.Direct Care Alliance: An advocacy group for direct care workers.National Domestic Workers Alliance

Thoughts on the Writing Process

This piece of writing has been a labor of love, and a tough nut to crack: I started writing this piece about twenty years ago as I worked in direct care, writing journal entries to help me process my experiences. I published a few articles in small magazines that explicitly called for change in the way that mental health was staffed in these centers. Then, I put it aside.

Thirteen years ago, I tried to approach it from a journalistic perspective and delved into this problem for my major project for a master's thesis in journalism on this topic at Ohio State University as part of the Kiplinger Fellowship Program. I queried many magazines but couldn't get interest because the topic seemed depressing and completely "unsexy." This fundamental unsexiness of women and low-wage work was so hard to write into, because it's a bedrock blind spot in our society. We take the presence of these workers for granted, so much so that this is the fabric of our society, the one we don't even comment on. We expect low-wage female workers to care for our bodies and our spirits when we falter and when we die.

Then, during my MFA program, I wrote the story again, from the memoir side, which resulted in an essay that was a finalist for an AWP "Intro" award and was later published in Kaleidoscope: A Journal of Disability Studies.

I pretty much gave up on it until last year, at which time I tipped the balance back and forth between memoir and journalism. The challenge was that I couldn't find a way to make it "light." Being less ranty is my cross to bear as a writer, and sometimes I apologize too much for ranting when I should just let it rip with a good old-fashioned harangue. Having done the work and having been a labor activist for a long time, I had lots of commitment to this issue. I wasn't a journalist who had gone into this as an investigation. I was first a patient, then a worker, then an activist, then a writer. Writing on subjects I care the most about--especially political subjects--has been a challenge when it comes to voice and tone.

The essay is a flexible form, and I believe the essay can contain not only dispassionate observation but also engagement and multiple emotions including anger. But "the essay" is often thought of as a bit distanced, maybe a bit removed, maybe even a bit arty. I love much of that stuff. I write some of it. However, I read many examples of the form that don't look like the essays I want to write, which is fine. For balance, and for encouragement, I have found it important to read and re-read to examples of engaged essayists like James Baldwin, Jamaica Kincaid, Joy Williams, Rebecca Solnit, George Orwell, and Cherrie Moraga, as well as my recent favorite Kiese Laymon. I like my essays troubled and even sometimes downright mad.

What is an essay? Can it include hot-button, yell-out, pissed-off? Can it have an agenda? Is it marked only by formal experimentation or reflection on a subject whose sting has faded with the passage of time? We shouldn't confuse the full breadth of possibilities in an essay with a narrowed sense of the role or voice of the average essay. While distance and perspective are important, it is sometimes impossible in a practical sense to step away from one's vivid emotions. If your topic itself is a large social problem, that topic and its resultant pain will persist over time. Does this mean you should not be an essayist? No--on the contrary, I think. I believe the world needs more essayists and essays that trouble their subjects--not at the surface level of form or fragmentation (though that is fine too, and all respect to those who do that work), but at the deep level of wrestling with a topic, coming away from that topic changed, acknowledging that the topic itself is bigger than the author.

Update: Here's a blog post I wrote over at the Direct Care Alliance on this book!

Thanks for reading. And check out all the great titles at